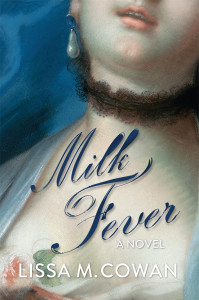

Postpartum depression has been misunderstood for centuries. Today I’m happy to share a guest post from Lissa Cowan, whose novel “Milk Fever” shares a perspective on postpartum depression from the 18th century.

Milk Fever is set in the eighteenth century at a time when women were viewed as inferior to men both intellectually and physically. The familiar historical expression “the weaker sex” helps us to understand how men and society in general viewed women during the Enlightenment. Medical textbooks portrayed women as emotionally sensitive, high strung and morally inferior. Armande, my main character, is a wet nurse who, after she has her baby, is struck with postpartum depression.

The next day, a feeling of foreboding drifted over me. Margot said this sometimes happens to new mothers. As an antidote to my melancholia, she instructed me to walk in the garden and meditate on God. These quiet times only caused me to be prey to my own distressing chatter.

At the time, women with postpartum depression had no language to describe their feelings and no support network to help them deal with their emotional difficulties. Today, we know that support is a key factor to recovery, yet back then not only did women not have any support, they were also shamed by others for their inability to mother as they should after giving birth. In my novel, Armande, an educated woman with a strong sense of self, is still swayed by the culture and society she lives in.

That woman is naturally committed to her offspring, that motherhood is a gift from the gods who bestow upon the fairer sex the most delightful experiences, is a philosopher’s flight of fancy. The fact is, though I would not admit it to a living soul, a part of me longed to be relieved of my shrieking and odorous destiny. I washed the child and no sooner did I replace the napkin with ties at the side than she soiled herself again. I held as truths Rousseau’s ideas about motherhood being the equivalent to bliss, yet I now felt that my existence was an illustration of despair. I know I am not the only mother who feels this way.

Let the truth be known: sometimes we mothers are sad, worse even. Sometimes we are nothing at all and are told we have no earthly reason to be thus. You’re a woman. And woman must bear fruit and be glad for it. How could I express sentiments of sadness at being a mother? I’ve nobody to turn to but the extension of myself that I rock back and forth, this bit of breath that clings to me for survival.

Armande has the support of her midwife who encourages her to take care of herself, allows her to rest and doesn’t make her feel that she is a bad mother. Yet in the real world of the 18th century, depression in women was seriously misunderstood and misdiagnosed. As an example, in “D’Alembert’s Dream,” written by 18th century French philosopher Denis Diderot, a fictional Dr. Bordeu presents a woman’s symptoms as he sees them following the birth of her child.

There was a woman who had just given birth to a child; as a result, she suffered a most alarming attack of the vapors—compulsive tears and laughter, a sense of suffocation, convulsions, swelling of the breasts, melancholy silence, piercing shrieks—all the most serious symptoms—and this went on for several years.

The doctor goes on to describe how she supposedly cured herself because she was afraid her lover would tire of her moods. For her consciousness to maintain the upper hand, she took on a conquer-or-die attitude, engaging in several forms of physical exercise until she was cured.

Whenever the rebellion began in her fibers she was able to feel it coming on. She would stand up, run about, busy herself with the most vigorous forms of physical exercise, climb up and down stairs, saw wood or shovel dirt.

It wasn’t until the 1850s that medical science first recognized postpartum depression as a disorder. Before that, abstract terms such as “wandering womb,” which dates back to Hippocrates, made it seem as though a woman’s body was betraying her and leading her emotions astray. This term referred to when the uterus was displaced and would lead to certain pathologies in women. A century later we would hear about women who experienced depression as being neurotic, and the familiar term “wandering womb” was re-coined as “hysteria.” Women who divulged their feelings of depression were often susceptible to strange experimental treatments and widespread ridicule. During the 1950s, electroshock therapy became a popular way for the medical establishment to treat depression in women and keep their so-called neuroses in check.

Today, we know there is no one trigger for postpartum depression, that it is very serious and that early detection is key to women eventually overcoming the disorder. Yet, even in the early 21st century the disorder continues to be under-diagnosed and some of the age-old archetypes, such as women being emotionally unstable or unfit mothers, still persist. Hopefully with increased awareness, education and outreach, women will no longer feel shame and alone in their emotional struggles. Like the midwife Margot who provided love and support to Armande at her time of greatest need, women need to support each other, to hear each others’ stories of pregnancy, birth, depression, and to be there—as sister, mother, therapist, doctor, social worker, psychologist, friend—no matter what it takes.

Lissa M. Cowan is the author of works of non-fiction, and her writing has appeared in Canadian and U.S. magazines and newspapers. She speaks and writes about storytelling, creativity, work-life balance and creative spirituality. She has received awards for her writing and “Milk Fever” is her first novel. Visit her novel page or find her on Twitter or Facebook.